Badminton

Badminton is a racquet sport played by either two opposing players (singles) or two opposing pairs (doubles), who take positions on opposite halves of a rectangular court that is divided by a net. Players score points by striking a shuttlecock with their racquet so that it passes over the net and lands in their opponents' half of the court. A rally ends once the shuttlecock has struck the ground, and the shuttlecock may only be struck once by each side before it passes over the net.

The shuttlecock is a feathered projectile whose unique aerodynamic properties cause it to fly differently from the balls used in most racquet sports; in particular, the feathers create much higher drag, causing the shuttlecock to decelerate more rapidly than a ball. Because shuttlecock flight is strongly affected by wind, competitive badminton is always played indoors. Badminton is also played outdoors as a casual recreational activity, often as a garden or beach game.

Badminton is an Olympic sport with five competitive disciplines: men's and women's singles, men's and women's doubles, and mixed doubles, in which each pair is a man and a woman. At high levels of play, the sport demands excellent fitness: players require aerobic stamina, strength, and speed. It is also a technical sport, requiring good motor coordination and the development of sophisticated racket skills.

Contents

|

[edit] History and development

Badminton was known in ancient times; an early form of the sport was played in ancient Greece and Egypt. In Japan, the related game Hanetsuki was played as early as the 16th century. In the west, badminton came from a game called battledore and shuttlecock, in which two or more players keep a feathered shuttlecock in the air with small rackets. The game was called "Poona" in India during the 18th century, and British Army officers stationed there took a competitive Indian version back to England in the 1860's, where it was played at country houses as an upper class amusement. Isaac Spratt, a London toy dealer, published a booklet, "Badminton Battledore - a new game" in 1860, but unfortunately no copy has survived.[2]

The new sport was definitively launched in 1873 at the Badminton House, Gloucestershire, owned by the Duke of Beaufort. During that time, the game was referred to as "The Game of Badminton," and, the game's official name became Badminton.[3]

Until 1887 the sport was played in England under the rules that prevailed in India. The Bath Badminton Club standardized the rules and made the game applicable to English ideas. The basic regulations were drawn up in 1887.[3] In 1893, the Badminton Association of England published the first set of rules according to these regulations, similar to today's rules, and officially launched badminton in a house called "Dunbar" at 6 Waverley Grove, Portsmouth, England on September 13 of that year.[4] They also started the All England Open Badminton Championships, the first badminton competition in the world, in 1899.

The Badminton World Federation (BWF) was established in 1934 with Canada, Denmark, England, France, the Netherlands, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland, and Wales as its founding members. India joined as an affiliate in 1936. The BWF now governs international badminton and develops the sport globally.[5]

While originated in England, international badminton has traditionally been dominated by a few Asian countries, plus Denmark from Europe. China, Indonesia, South Korea and Malaysia are among the nations that have consistently produced world-class players in the past few decades and dominated competitions on the international level, with China being the most dominant in recent years.[6]

[edit] Laws of the game

The following information is a simplified summary of the Laws, not a complete reproduction. The definitive source of the Laws is the IBF Laws publication,[7] although the digital distribution of the Laws contains poor reproductions of the diagrams.

[edit] Playing court dimensions

The court is rectangular and divided into halves by a net. Courts are almost always marked for both singles and doubles play, although the laws permit a court to be marked for singles only. The doubles court is wider than the singles court, but both are the same length. The exception, which often causes confusion to newer players is the doubles court has a shorter serve-length dimension.

The full width of the court is 6.1 metres (20 ft), and in singles this width is reduced to 5.18 metres (17 ft). The full length of the court is 13.4 metres (44 ft). The service courts are marked by a centre line dividing the width of the court, by a short service line at a distance of 1.98 metres (6.5 ft) from the net, and by the outer side and back boundaries. In doubles, the service court is also marked by a long service line, which is 0.78 metres (2 ft 6 inch) from the back boundary.

The net is 1.55 metres (5 ft 1 inch) high at the edges and 1.524 metres (5 ft) high in the centre. The net posts are placed over the doubles side lines, even when singles is played.

There is no mention in the Laws of badminton, of a minimum height for the ceiling above the court. Nonetheless, a badminton court will not be suitable if the ceiling is likely to be hit on a high serve.

[edit] Equipment laws

The Laws specify which equipment may be used. In particular, the Laws restrict the design and size of rackets and shuttlecocks. The Laws also provide for testing a shuttlecock for the correct speed:

- 3.1

- To test a shuttlecock, use a full underhand stroke which makes contact with the shuttlecock over the back boundary line. The shuttlecock shall be hit at an upward angle and in a direction parallel to the side lines.

- 3.2

- A shuttlecock of the correct speed will land not less than 530 mm and not more than 990 mm short of the other back boundary line....

[edit] Scoring system and service

The scoring system changed in May 2006. For more information, see Scoring System Development of Badminton.

[edit] The basics

Each game is played up to 21 points, with players scoring a point whenever they win a rally (this differs from the old system, where players could only win a point on their serve). A match is the best of three games.

At the start of the rally, the server and receiver stand in diagonally opposite service courts (see court dimensions). The server hits the shuttlecock so that it would land in the receiver's service court. This is similar to tennis, except that a badminton serve must be hit from below the waist in underhand form (upwards), the shuttlecock is not allowed to bounce, and in tennis the players stand outside their service courts.

In singles, the server stands in his right service court when his score is even, and in his left service court when his score is odd.

In doubles, if the serving side wins a rally, the same player continues to serve, but he changes service courts so that he serves to each opponent in turn. When the serving side loses a rally, the serve passes to their opponents (unlike the old system, there is no "second serve"). If their new score is even, the player in the right service court serves; if odd, the player in the left service court serves. The players' service courts are determined by their positions at the start of the previous rally, not by where they were standing at the end of the rally.

A consequence of this system is that, each time a side regain the service, the server will be the player who did not serve last time.

[edit] Details

When the server serves, the shuttlecock must pass over the service line or it will count as a fault.

If the score reaches 20-all, then the game continues until one side gains a two point lead (such as 24-22), up to a maximum of 30 points (30-29 is a winning score).

At the start of a match a coin is tossed. The winners of the coin toss may choose whether to serve or receive first, or they may choose which end of the court they wish to occupy. Their opponents make the remaining choice. In less formal settings, the coin toss is often replaced by hitting a shuttlecock into the air: whichever side it points to serves first.

In subsequent games, the winners of the previous game serve first. For the first rally of any doubles game, the serving pair may decide who serves and the receiving pair may decide who receives. The players change ends at the start of the second game; if the match reaches a third game, they change ends both at the start of the game and when the leading pair's score reaches 11 points.

The server and receiver must remain within their service courts, without touching the boundary lines, until the server strikes the shuttlecock. The other two players may stand wherever they wish, so long as they do not unsight the opposing server or receiver.

[edit] Faults

Players win a rally by striking the shuttlecock onto the floor within the boundaries of their opponents' court. Players also win a rally if their opponents commit a fault. The most common fault in badminton is when the players fail to return the shuttlecock so that it passes over the net and lands inside their opponents' court, but there are also other ways that players may be faulted. The following information lists some of the more common faults.

Several faults pertain specifically to service. A serving player shall be faulted if he strikes the shuttlecock from above his waist (defined as his lowest rib), or if his racket is not pointing downwards at the moment of impact. This particular law was modified in 2006: previously, the server's racket had to be pointing downwards to the extent that the racket head was below the hand holding the racket; now, any angle below the horizontal is acceptable.

Neither the server nor the receiver may lift a foot until the shuttlecock has been struck by the server. The server must also initially hit the base (cork) of the shuttlecock, although he may afterwards also hit the feathers as part of the same stroke. This law was introduced to ban an extremely effective service style known as the S-serve or Sidek serve, which allowed the server to make the shuttlecock spin chaotically in flight.[8]

Each side may only strike the shuttlecock once before it passes back over the net; but during a single stroke movement, a player may contact a shuttlecock twice (this happens in some sliced shots). A player may not, however, hit the shuttlecock once and then hit it with a new movement, nor may he carry and sling the shuttlecock on his racket.

It is a fault if the shuttlecock hits the ceiling.

[edit] Lets

If a let is called, the rally is stopped and replayed with no change to the score. Lets may occur due to some unexpected disturbance such as a shuttlecock landing on court (having been hit there by players on an adjacent court).

If the receiver is not ready when the service is delivered, a let shall be called; yet if the receiver makes any attempt to return the shuttlecock, he shall be judged to have been ready.

There is no let if the shuttlecock hits the tape (even on service).

[edit] Equipment

[edit] Rackets

Badminton rackets are light, with top quality rackets weighing between about 70 and 100 grams (without strings). [9][10] They are composed of many different materials ranging from carbon fibre composite (graphite reinforced plastic) to solid steel, which may be augmented by a variety of materials. Carbon fibre has an excellent strength to weight ratio, is stiff, and gives excellent kinetic energy transfer. Before the adoption of carbon fibre composite, rackets were made of light metals such as aluminium. Earlier still, rackets were made of wood. Cheap rackets are still often made of metal, but wooden rackets are no longer manufactured for the ordinary market, due to their excessive weight and cost.

There is a wide variety of racket designs, although the racket size and shape are limited by the Laws. Different rackets have playing characteristics that appeal to different players. The traditional oval head shape is still available, but an isometric head shape is increasingly common in new rackets.

[edit] Strings

Badminton strings are thin, high performing strings in the range of about 0.65 to 0.73 millimetres thickness. Thicker strings are more durable, but many players prefer the feel of thinner strings. String tension is normally in the range of 18 to 36 lbf (80 to 130 newtons). Recreational players generally string at lower tensions than professionals, typically between 18 and 25 lbf. Professionals string between about 25 and 36 lbf.

It is often argued that high string tensions improve control, whereas low string tensions increase power.[11] The arguments for this generally rely on crude mechanical reasoning, such as claiming that a lower tension stringbed is more bouncy and therefore provides more power. An alternative view suggests that the optimum tension for power depends on the player:[12] the faster and more accurately a player can swing their racket, the higher the tension for maximum power. Neither view has been subjected to a rigorous mechanical analysis, nor is there clear evidence in favour of one or the other. The most effective way for a player to find a good string tension is to experiment. Playing at high string tensions can cause injury, depending on the player's ability: few amateur players can safely play above 30 lbf, and for most players even 25 lbf is too high.

[edit] Grip

The choice of grip allows a player to increase the thickness of his racket handle and choose a comfortable surface to hold. A player may build up the handle with one or several grips before applying the final layer.

Players may choose between a variety of grip materials. The most common choices are PU synthetic grips or toweling grips. Grip choice is a matter of personal preference. Players often find that sweat becomes a problem; in this case, a drying agent may be applied to the grip or hands, or sweatbands may be used, or the player may choose another grip material or change his grip more frequently.

There are two main types of grip: replacement grips and overgrips. Replacement grips are thicker, and are often used to increase the size of the handle. Overgrips are thinner (less than 1 mm), and are often used as the final layer. Many players, however, prefer to use replacement grips as the final layer. Toweling grips are always replacement grips. Replacement grips have an adhesive backing, whereas overgrips have only a small patch of adhesive at the start of the tape and must be applied under tension; overgrips are more convenient for players who change grips frequently, because they may be removed more rapidly without damaging the underlying material.

[edit] Shuttlecock

- Main article: Shuttlecock

A shuttlecock (often abbreviated to shuttle and also known as a bird or birdie) is a high-drag projectile, with an open conical shape: the cone is formed from sixteen overlapping goose feathers embedded into a rounded cork base. The cork is covered with thin leather.

Shuttles with a plastic skirt are often used by recreational players to reduce their costs: feathered shuttles break easily.

[edit] Shoes

Badminton shoes are lightweight with soles of rubber or similar high-grip, non-marking materials.

Compared to running shoes, badminton shoes have little lateral support. High levels of lateral support are useful for activities where lateral motion is undesirable and unexpected. Badminton, however, requires powerful lateral movements. A highly built-up lateral support will not be able to protect the foot in badminton; instead, it will encourage catastrophic collapse at the point where the shoe's support fails, and the player's ankles are not ready for the sudden loading. For this reason, players should choose badminton shoes rather than general trainers or running shoes. Players should also ensure that they learn safe footwork, with the knee and foot in alignment on all lunges.

[edit] Badminton strokes

Badminton offers a wide variety of basic strokes, and players require a high level of skill to perform all of them effectively. All strokes can be played either forehand or backhand (except for the high serve, which is only ever played as a forehand). A player's forehand side is the same side as his playing hand: for a right-handed player, the forehand side is his right side and the backhand side is his left side. Forehand strokes are hit with the front of the hand leading (like hitting with the palm), whereas backhand strokes are hit with the back of the hand leading (like hitting with the knuckles). Players frequently play certain strokes on the forehand side with a backhand hitting action, and vice-versa.

In the forecourt and midcourt, most strokes can be played equally effectively on either the forehand or backhand side; but in the rearcourt, players will attempt to play as many strokes as possible on their forehands, often preferring to play a round-the-head forehand overhead (a forehand "on the backhand side") rather than attempt a backhand overhead. Playing a backhand overhead has two main disadvantages. First, the player must turn his back to his opponents, restricting his view of them and the court. Second, backhand overheads cannot be hit with as much power as forehands: the hitting action is limited by the shoulder joint, which permits a much greater range of movement for a forehand overhead than for a backhand. The backhand clear is considered by most players and coaches to be the most difficult basic stroke in the game, since precise technique is needed in order to muster enough power for the shuttlecock to travel the full length of the court. For the same reason, backhand smashes tend to be weak.

The choice of stroke depends on how near the shuttlecock is to the net, and whether it is above net height: players have much better attacking options if they can reach the shuttlecock well above net height, especially if it is also close to the net. In the forecourt, a high shuttlecock will be met with a net kill, hitting it steeply downwards and attempting to win the rally immediately. In the midcourt, a high shuttlecock will usually be met with a powerful smash, also hitting downwards and hoping for an outright winner or a weak reply. Athletic jump smashes, where players jump upwards for a steeper smash angle, are a common and spectacular element of elite men's doubles play. In the rearcourt, players strive to hit the shuttlecock while it is still above them, rather than allowing it to drop lower. This overhead hitting allows them to play smashes, clears (hitting the shuttlecock high and to the back of the opponents' court), and dropshots (hitting the shuttlecock so that it falls softly downwards into the opponents' forecourt). If the shuttlecock has dropped lower, then a smash is impossible and a full-length, high clear is difficult.

When the shuttlecock is well below net height, players have no choice but to hit upwards. Lifts, where the shuttlecock is hit upwards to the back of the opponents' court, can be played from all parts of the court. If a player does not lift, his only remaining option is to push the shuttlecock softly back to the net: in the forecourt this is called a netshot; in the midcourt or rearcourt, it is often called a push or block.

When the shuttlecock is near to net height, players can hit drives, which travel flat and rapidly over the net into the opponents' rear midcourt and rearcourt. Pushes may also be hit flatter, placing the shuttlecock into the front midcourt. Drives and pushes may be played from the midcourt or forecourt, and are most often used in doubles: they are an attempt to regain the attack, rather than choosing to lift the shuttlecock and defend against smashes. After a successful drive or push, the opponents will often be forced to lift the shuttlecock.

When defending against a smash, players have three basic options: lift, block, or drive. In singles, a block to the net is the most common reply. In doubles, a lift is the safest option but it usually allows the opponents to continue smashing; blocks and drives are counter-attacking strokes, but may be intercepted by the smasher's partner. Many players use a backhand hitting action for returning smashes on both the forehand and backhand sides, because backhands are more effective than forehands at covering smashes directed to the body.

The service presents its own array of stroke choices. Unlike in tennis, the serve is restricted by the Laws so that it must be hit upwards. The server can choose a low serve into the forecourt (like a push), or a lift to the back of the service court, or a flat drive serve. Lifted serves may be either high serves, where the shuttlecock is lifted so high that it falls almost vertically at the back of the court, or flick serves, where the shuttlecock is lifted to a lesser height but falls sooner.

Once players have mastered these basic strokes, they can hit the shuttlecock from and to any part of the court, powerfully and softly as required. Beyond the basics, however, badminton offers rich potential for advanced stroke skills that provide a competitive advantage. Because badminton players have to cover a short distance as quickly as possible, the purpose of many advanced strokes is to deceive the opponent, so that either he is tricked into believing that a different stroke is being played, or he is forced to delay his movement until he actually sees the shuttle's direction. "Deception" in badminton is often used in both of these senses. When a player is genuinely deceived, he will often lose the point immediately because he cannot change his direction quickly enough to reach the shuttlecock. Experienced players will be aware of the trick and cautious not to move too early, but the attempted deception is still useful because it forces the opponent to delay his movement slightly. Against weaker players whose intended strokes are obvious, an experienced player will move before the shuttlecock has been hit, anticipating the stroke to gain an advantage.

Slicing and using a shortened hitting action are the two main technical devices that facilitate deception. Slicing involves hitting the shuttlecock with an angled racket face, causing it to travel in a different direction than suggested by the body or arm movement. Slicing also causes the shuttlecock to travel much slower than the arm movement suggests. For example, a good crosscourt sliced dropshot will use a hitting action that suggests a straight clear or smash, deceiving the opponent about both the power and direction of the shuttlecock. A more sophisticated slicing action involves brushing the strings around the shuttlecock during the hit, in order to make the shuttlecock spin. This can be used to improve the shuttle's trajectory, by making it dip more rapidly as it passes the net; for example, a sliced low serve can travel slightly faster than a normal low serve, yet land on the same spot. Spinning the shuttlecock is also used to create spinning netshots (also called tumbling netshots), in which the shuttlecock turns over itself several times (tumbles) before stabilizing; sometimes the shuttlecock remains inverted instead of tumbling. The main advantage of a spinning netshot is that the opponent will be unwilling to address the shuttlecock until it has stopped tumbling, since hitting the feathers will result in an unpredictable stroke. Spinning netshots are especially important for high level singles players.

The lightness of modern rackets allows players to use a very short hitting action for many strokes, thereby maintaining the option to hit a powerful or a soft stroke until the last possible moment. For example, a singles player may hold his racket ready for a netshot, but then flick the shuttlecock to the back instead with a shallow lift. This makes the opponent's task of covering the whole court much more difficult than if the lift was hit with a bigger, obvious swing. A short hitting action is not only useful for deception: it also allows the player to hit powerful strokes when he has no time for a big arm swing. The use of grip tightening is crucial to these techniques, and is often described as finger power. Elite players develop finger power to the extent that they can hit some power strokes, such as net kills, with less than a 10 cm racket swing.

It is also possible to reverse this style of deception, by suggesting a powerful stroke before slowing down the hitting action to play a soft stroke. In general, this latter style of deception is more common in the rearcourt (for example, dropshots disguised as smashes), whereas the former style is more common in the forecourt and midcourt (for example, lifts disguised as netshots).

Deception is not limited to slicing and short hitting actions. Players may also use double motion, where they make an initial racket movement in one direction before withdrawing the racket to hit in another direction. This is typically used to suggest a crosscourt angle but then play the stroke straight, or vice-versa. Triple motion is also possible, but this is very rare in actual play. An alternative to double motion is to use a racket head fake, where the initial motion is continued but the racket is turned during the hit. This produces a smaller change in direction, but does not require as much time.

[edit] Strategy

To win in badminton, players need to employ a wide variety of strokes in the right situations. These range from powerful jumping smashes to delicate tumbling net returns. Often rallies finish with a smash, but setting up the smash requires subtler strokes. For example, a netshot can force the opponent to lift the shuttlecock, which gives an opportunity to smash. If the netshot is tight and tumbling, then the opponent's lift will not reach the back of the court, which makes the subsequent smash much harder to return.

Deception is also important. Expert players make the preparation for many different strokes look identical, and use slicing to deceive their opponents about the speed or direction of the stroke. If an opponent tries to anticipate the stroke, he may move in the wrong direction and may be unable to change his body momentum in time to reach the shuttlecock.

[edit] Doubles

Both pairs will try to gain and maintain the attack, hitting downwards as much as possible. Whenever possible, a pair will adopt an ideal attacking formation with one player hitting down from the rearcourt, and his partner in the midcourt intercepting all smash returns except the lift. If the rearcourt attacker plays a dropshot, his partner will move into the forecourt to threaten the net reply. If a pair cannot hit downwards, they will use flat strokes in an attempt to gain the attack. If a pair is forced to lift or clear the shuttlecock, then they must defend: they will adopt a side-by-side position in the rear midcourt, to cover the full width of their court against the opponents' smashes.

At high levels of play, the backhand serve has become popular to the extent that forehand serves almost never appear in professional games. The straight low serve is used most frequently, in an attempt to prevent the opponents gaining the attack immediately. Flick serves are used to prevent the opponent from anticipating the low serve and attacking it decisively.

At high levels of play, doubles rallies are extremely fast. Men's doubles is the most aggressive form of badminton, with a high proportion of powerful jump smashes.

[edit] Singles

The singles court is narrower than the doubles court, but the same length. Since one person needs to cover the entire court, singles tactics are based on forcing the opponent to move as much as possible; this means that singles strokes are normally directed to the corners of the court. Players exploit the length of the court by combining lifts and clears with dropshots and netshots. Smashing is less prominent in singles than in doubles because players are rarely in the ideal position to execute a smash, and smashing often leaves the smasher vulnerable if the smash is returned.

In singles, players will often start the rally with a forehand high serve. Low serves are also used frequently, either forehand or backhand. Flick serves are less common, and drive serves are rare.

At high levels of play, singles demands extraordinary fitness. Singles is a game of patient positional maneuvering, unlike the all-out aggression of doubles.

[edit] Mixed doubles

In mixed doubles, both pairs try to maintain an attacking formation with the woman at the front and the man at the back. This is because the male players are substantially stronger, and can therefore produce more powerful smashes. As a result, mixed doubles requires greater tactical awareness and subtler positional play. Clever opponents will try to reverse the ideal position, by forcing the woman towards the back or the man towards the front. In order to protect against this danger, mixed players must be careful and systematic in their shot selection.[13]

At high levels of play, the formations will generally be more flexible: the top women players are capable of playing powerfully from the rearcourt, and will happily do so if required. When the opportunity arises, however, the pair will switch back to the standard mixed attacking position, with the woman in front.

[edit] Governing bodies

The Badminton World Federation (BWF) is the internationally recognised governing body of the sport. The BWF headquarters are currently located in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Five regional confederations are associated with the IBF:

- Asia: Badminton Asia Confederation (BAC)

- Africa: Africa Badminton Federation (ABF)

- Americas: Badminton Pan Am (North America and South America belong to the same confederation; BPA)

- Europe: Badminton Europe (BE)

- Oceania: Badminton Oceania (BO)

[edit] Competitions

The BWF organizes several international competitions, including the Thomas Cup, the premier men's event, and the Uber Cup, the women's equivalent. The competitions take place once every two years. More than 50 national teams compete in qualifying tournaments within continental confederations for a place in the finals. The final tournament involves 12 teams, following an increase from eight teams in 2004.

The Sudirman Cup, a mixed team event held once every two years, began in 1989. It is divided into seven groups based on the performance of each country. To win the tournament, a country must perform well across all five disciplines (men's doubles and singles, women's doubles and singles, and mixed doubles). Like soccer, it features a promotion and relegation system in every group.

Individual competition in badminton was a demonstration event in the 1972 and 1988 Summer Olympics. It became a Summer Olympics sport at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992. The 32 highest ranked badminton players in the world participate in the competition, and each country submitting three players to take part. In the BWF World Championships, only the highest ranked 64 players in the world, and a maximum of three from each country, can participate in any category.

All these tournaments, along with the BWF World Junior Championships, are level one tournaments.

At the start of 2007, the BWF also introduce a new tournament structure: the BWF Super Series. This level two tournament will stage twelve open tournaments around the world with 32 players (half the previous limit). The players collect points that determine whether they can play in Super Series Final held at the year end.[14][15]

Level three tournaments will consist of Grand Prix Gold and Grand Prix. Top players can collect the world ranking points and enable them to play in the BWF Super Series open tournaments. These include the regional competitions in Asia (Badminton Asia Championships) and Europe (European Badminton Championships), which produce the world's best players as well as the Pan America Badminton Championships.

The level four tournaments, known as International Challenge, International Series and Future Series, encourages participation by junior players.[16]

[edit] Records

The most powerful stroke in badminton is the smash, which is hit steeply downwards into the opponents' midcourt. The maximum speed of a smashed shuttlecock exceeds that of any other racket sport projectile. The recordings of this speed measure the initial speed of the shuttlecock immediately after it has left the player's racket.

Men's doubles player Fu Haifeng of China set the official world smash record of 332 km/h (206 mph) on June 3, 2005 in the Sudirman Cup. The fastest smash recorded in the singles competition is 305 km/h (189 mph) by Taufik Hidayat of Indonesia.[17]

[edit] Comparisons with other racket sports

Badminton is frequently compared to tennis. The following is a list of uncontentious comparisons:

- In tennis, the ball may bounce once before the player hits it; in badminton, the rally ends once the shuttlecock touches the floor.

- In tennis, the serve is dominant to the extent that the server is expected to win most of his service games; a break of service, where the server loses the game, is of major importance in a match. In badminton, however, the serving side and receiving side have approximately equal opportunity to win the rally.

- In tennis, the server is allowed two attempts to make a correct serve; in badminton, the server is allowed only one attempt.

- In tennis, a let is played on service if the ball hits the net tape; in badminton, there is no let on service.

- The tennis court is larger than the badminton court.

- Tennis rackets are about four times heavier than badminton rackets, 10-12 ounces (approximately 284-340 grams) versus 85-93 grams.[18][19] Tennis balls are about 10 times heavier than shuttlecocks, 57 grams versus 5 grams.[20][21]

- The fastest recorded tennis stroke is Andy Roddick's 153 mph (246 km/h) serve;[22] the fastest recorded badminton stroke is Fu Haifeng's 206 mph (332 km/h) smash.[23]

[edit] Comparisons of speed and athletic requirements

Statistics such as the 206 mph (332 km/h) smash speed, below, prompt badminton enthusiasts to make other comparisons that are more contentious. For example, it is often claimed that badminton is the fastest racket sport.[24] Although badminton holds the record for the fastest initial speed of a racket sports projectile, the shuttlecock decelerates substantially faster than other projectiles such as tennis balls. In turn, this qualification must be qualified by consideration of the distance over which the shuttlecock travels: a smashed shuttlecock travels a shorter distance than a tennis ball during a serve. Badminton's claim as the fastest racket sport might also be based on reaction time requirements, but arguably table tennis requires even faster reaction times.

There is a strong case for arguing that badminton is more physically demanding than tennis, but such comparisons are difficult to make objectively due to the differing demands of the games. Some informal studies suggest that badminton players require much greater aerobic stamina than tennis players, but this has not been the subject of rigorous research.[25]

A more balanced approach might suggest the following comparisons, although these also are subject to dispute:

- Badminton, especially singles, requires substantially greater aerobic stamina than tennis; the level of aerobic stamina required by badminton singles is similar to squash singles, although squash may have slightly higher aerobic requirements.

- Tennis requires greater upper body strength than badminton.

- Badminton requires greater leg strength than tennis, and badminton men's doubles probably requires greater leg strength than any other racket sport due to the demands of performing multiple consecutive jumping smashes.

- Badminton requires much greater explosive athleticism than tennis and somewhat greater than squash, with players required to jump for height or distance.

- Badminton requires significantly faster reaction times than either tennis or squash, although table tennis may require even faster reaction times. The fastest reactions in badminton are required in men's doubles, when returning a powerful smash.

[edit] Comparisons of technique

Badminton and tennis techniques differ substantially. The lightness of the shuttlecock and of badminton rackets allow badminton players to make use of the wrist and fingers much more than tennis players; in tennis the wrist is normally held stable, and playing with a mobile wrist may lead to injury. For the same reasons, badminton players can generate power from a short racket swing: for some strokes such as net kills, an elite player's swing may be less than 10cm. For strokes that require more power, a longer swing will typically be used, but the badminton racket swing will rarely be as long as a typical tennis swing.

It is often asserted that power in badminton strokes comes mainly from the wrist. This is a misconception and may be criticised for two reasons. First, it is strictly speaking a category error: the wrist is a joint, not a muscle; its movement is controlled by the forearm muscles. Second, wrist movements are weak when compared to forearm or upper arm movements. Badminton biomechanics have not been the subject of extensive scientific study, but some studies confirm the minor role of the wrist in power generation, and indicate that the major contributions to power come from internal and external rotations of the upper and lower arm.[26] Modern coaching resources such as the Badminton England Technique DVD reflect these ideas by emphasising forearm rotation rather than wrist movements.[27]

[edit] Distinctive characteristics of the shuttlecock

The shuttlecock differs greatly from the balls used in most other racket sports.

[edit] Aerodynamic drag and stability

The feathers impart substantial drag, causing the shuttlecock to decelerate greatly over distance. The shuttlecock is also extremely aerodynamically stable: regardless of initial orientation, it will turn to fly cork-first, and remain in the cork-first orientation.

One consequence of the shuttlecock's drag is that it requires considerable skill to hit it the full length of the court, which is not the case for most racket sports. The drag also influences the flight path of a lifted (lobbed) shuttlecock: the parabola of its flight is heavily skewed so that it falls at a steeper angle than it rises. With very high serves, the shuttlecock may even fall vertically.

[edit] Spin

Balls may be spun to alter their bounce (for example, topspin and backspin in tennis), and players may slice the ball (strike it with an angled racket face) to produce such spin; but, since the shuttlecock is not allowed to bounce, this does not apply to badminton.

Slicing the shuttlecock so that it spins, however, does have applications, and some are peculiar to badminton. (See Basic strokes for an explanation of technical terms.)

- Slicing the shuttlecock from the side may cause it to travel in a different direction from the direction suggested by the player's racket or body movement. This is used to deceive opponents.

- Slicing the shuttlecock from the side may cause it to follow a slightly curved path (as seen from above), and the deceleration imparted by the spin causes sliced strokes to slow down more suddenly towards the end of their flight path. This can be used to create dropshots and smashes that dip more steeply after they pass the net.

- When playing a netshot, slicing underneath the shuttlecock may cause it to turn over itself (tumble) several times as it passes the net. This is called a spinning netshot or tumbling netshot. The opponent will be unwilling to address the shuttlecock until it has corrected its orientation.

Due to the way that its feathers overlap, a shuttlecock also has a slight natural spin about its axis of rotational symmetry. The spin is in an anticlockwise direction as seen from above when dropping a shuttlecock. This natural spin affects certain strokes: a tumbling netshot is more effective if the slicing action is from right to left, rather than from left to right.[28]

Basketball

| Basketball | |

| |

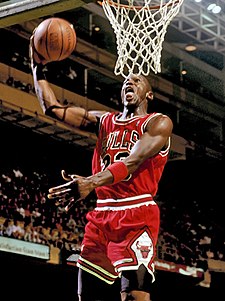

| Michael Jordan goes for a slam dunk | |

| Highest governing body | FIBA |

| First played | 1891, Springfield, Massachusetts, (USA) |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Contact |

| Team Members | 12 to 15 (5 at a time) |

| Mixed Gender | Single |

| Category | Indoor |

| Ball | Basketball |

| Olympic | 1936 |

Basketball is a team sport in which two teams of five active players each try to score points against one another by throwing a ball through a 10 feet (3 m) high hoop (the goal) under organized rules. Basketball is one of the most popular and widely viewed sports in the world.

Points are scored by shooting the ball through the basket from above; the team with more points at the end of the game wins. The ball can be advanced on the court by bouncing it (dribbling) or passing it between teammates. Disruptive physical contact (fouls) is not permitted and there are restrictions on how the ball can be handled (violations).

Through time, basketball has developed to involve common techniques of shooting, passing and dribbling, as well as players' positions, and offensive and defensive structures. While competitive basketball is carefully regulated, numerous variations of basketball have developed for casual play. In some countries, basketball is also a popular spectator sport.

While competitive basketball is primarily an indoor sport, played on a basketball court, less regulated variations have become exceedingly popular as an outdoor sport among both inner city and rural groups.

Contents

|

History

In early December 1891, Dr. James Naismith,[1] a Canadian physical education student and instructor at YMCA Training School[2] (today, Springfield College) in Springfield, Massachusetts, USA, sought a vigorous indoor game to keep his students occupied and at proper levels of fitness during the long New England winters. After rejecting other ideas as either too rough or poorly suited to walled-in gymnasiums, he wrote the basic rules and nailed a peach basket onto a 10-foot (3.05 m) elevated track. In contrast with modern basketball nets, this peach basket retained its bottom, and balls had to be retrieved manually after each "basket" or point scored, this proved inefficient, however, so a hole was drilled into the bottom of the basket, allowing the balls to be poked out with a long dowel each time. A further change was soon made, so the ball merely passed through, paving the way for the game we know today. A soccer ball was used to shoot goals. Whenever a person got the ball in the basket, they would give their team a point. Whichever team got the most points won the game. [3]

Naismith's handwritten diaries, discovered by his granddaughter in early 2006, indicate that he was nervous about the new game he had invented, which incorporated rules from a Canadian children's game called "Duck on a Rock", as many had failed before it. Naismith called the new game 'Basket Ball'.[4]

The first official basketball game was played in the YMCA gymnasium on January 20, 1892 with nine players, on a court just half the size of a present-day Streetball or National Basketball Association (NBA) court. "Basket ball", the name suggested by one of Naismith's students, was popular from the beginning.

Women's basketball began in 1892 at Smith College when Senda Berenson, a physical education teacher, modified Naismith's rules for women.

Basketball's early adherents were dispatched to YMCAs throughout the United States, and it quickly spread through the USA and Canada. By 1895, it was well established at several women's high schools. While the YMCA was responsible for initially developing and spreading the game, within a decade it discouraged the new sport, as rough play and rowdy crowds began to detract from the YMCA's primary mission. However, other amateur sports clubs, colleges, and professional clubs quickly filled the void. In the years before World War I, the Amateur Athletic Union and the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (forerunner of the NCAA) vied for control over the rules for the game.

Basketball was originally played with an association football ball. The first balls made specifically for basketball were brown, and it was only in the late 1950s that Tony Hinkle, searching for a ball that would be more visible to players and spectators alike, introduced the orange ball that is now in common use.

Dribbling was not part of the original game except for the "bounce pass" to teammates. Passing the ball was the primary means of ball movement. Dribbling was eventually introduced but limited by the asymmetric shape of early balls. Dribbling only became a major part of the game around the 1950s as manufacturing improved the ball shape.

Basketball, netball, dodgeball, volleyball, and lacrosse are the only ball games which have been identified as being invented by North Americans. Other ball games, such as baseball and Canadian football, have Commonwealth of Nations, European, Asian or African connections.

Although there is no direct evidence as yet that the idea of basketball came from the ancient Mesoamerican ballgame, knowledge of that game had been available for at least 50 years prior to Naismith's creation in the writings of John Lloyd Stephens and Alexander von Humboldt. Stephen's works especially, which included drawings by Frederick Catherwood, were available at most educational institutions in the 19th century and also had wide popular circulation.

College basketball and early leagues

Naismith was instrumental in establishing college basketball. Naismith coached at University of Kansas for six years before handing the reins to renowned coach Phog Allen. Naismith's disciple Amos Alonzo Stagg brought basketball to the University of Chicago, while Adolph Rupp, a student of Naismith's at Kansas, enjoyed great success as coach at the University of Kentucky. In 1892, University of California and Miss Head's School, played the first women's inter-institutional game. Berenson's freshmen played the sophomore class in the first women's collegiate basketball game at Smith College, March 21, 1893. The same year, Mount Holyoke and Sophie Newcomb College (coached by Clara Gregory Baer) women began playing basketball. By 1895, the game had spread to colleges across the country, including Wellesley, Vassar and Bryn Mawr. The first intercollegiate women's game was on April 4, 1896. Stanford women played Berkeley, 9-on-9, ending in a 2-1 Stanford victory. In 1901, colleges, including the University of Chicago, Columbia University, Dartmouth College, University of Minnesota, the U.S. Naval Academy, the University of Utah and Yale University began sponsoring men's games. By 1910, frequent injuries on the men's courts prompted President Roosevelt to suggest that college basketball form a governing body. And the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (IAAUS) was created.

Teams abounded throughout the 1920s. There were hundreds of men's professional basketball teams in towns and cities all over the United States and little organization of the professional game. Players jumped from team to team and teams played in armories and smoky dance halls. Leagues came and went. And barnstorming squads such as the Original Celtics and two all African American teams, the New York Renaissance Five ("Rens") and (still in existence as of 2006) the Harlem Globetrotters played up to two hundred games a year on their national tours. Women's basketball was more structured. In 1905, the National Women's Basketball Committee's Executive Committee on Basket Ball Rules was created by the American Physical Education Association. These rules called for six to nine players per team and 11 officials. The International Women's Sports Federation (1924) included a women's basketball competition. 37 women's high school varsity basketball or state tournaments were held by 1925. And in 1926, the Amateur Athletic Union backed the first national women's basketball championship, complete with men's rules. The first women's AAU All-America team was chosen in 1929. Women's industrial leagues sprang up throughout the nation, producing famous athletes like Babe Didrikson of the Golden Cyclones and the All American Red Heads Team who competed against men's teams, using men's rules. By 1938, the women's national championship changed from a three-court game to two-court game with six players per team. The first men's national championship tournament, the National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball tournament, which still exists as the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) tournament, was organized in 1937. The first national championship for NCAA teams, the National Invitation Tournament (NIT) in New York, was organized in 1938; the NCAA national tournament would begin one year later.

College basketball was rocked by gambling scandals from 1948 to 1951, when dozens of players from top teams were implicated in match fixing and point shaving. Partially spurred by an association with cheating, the NIT lost support to the NCAA tournament.

U.S. high school basketball

Before widespread school district consolidation, most United States high schools were far smaller than their present day counterparts. During the first decades of the 20th century, basketball quickly became the ideal interscholastic sport due to its modest equipment and personnel requirements. In the days before widespread television coverage of professional and college sports, the popularity of high school basketball was unrivaled in many parts of America.

Today virtually every high school in the United States fields a basketball team in varsity competition. Basketball's popularity remains high, both in rural areas where they carry the identification of the entire community, as well as at some larger schools known for their basketball teams where many players go on to participate at higher levels of competition after graduation. In the 2003–04 season, 1,002,797 boys and girls represented their schools in interscholastic basketball competition, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations. The states of Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky are particularly well known for their residents' devotion to high school basketball, commonly called Hoosier Hysteria in Indiana; the critically acclaimed film Hoosiers shows high school basketball's depth of meaning to these rural communities.

National Basketball Association

- Main article: National Basketball Association

In 1946, the Basketball Association of America (BAA) was formed, organizing the top professional teams and leading to greater popularity of the professional game. The first game was played in Toronto, Canada between the Toronto Huskies and New York Knickerbockers on November 1, 1946. Three seasons later, in 1949, the BAA became the National Basketball Association (NBA). An upstart organization, the American Basketball Association, emerged in 1967 and briefly threatened the NBA's dominance until the rival leagues merged in 1976. Today the NBA is the top professional basketball league in the world in terms of popularity, salaries, talent, and level of competition.

The NBA has featured many famous players, including George Mikan, the first dominating "big man"; ball-handling wizard Bob Cousy and defensive genius Bill Russell of the Boston Celtics; Wilt Chamberlain, who originally played for the barnstorming Harlem Globetrotters; all-around stars Oscar Robertson and Jerry West; more recent big men Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Karl Malone; playmaker John Stockton; crowd-pleasing forward Julius Erving; European stars Dirk Nowitzki and Drazen Petrovic and the three players who many credit with ushering the professional game to its highest level of popularity: Larry Bird, Earvin "Magic" Johnson, and Michael Jordan.

The NBA-backed Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) began 1997. Though it had an insecure opening season, several marquee players (Sheryl Swoopes, Lisa Leslie and Sue Bird among others) helped the league's popularity and level of competition. Other professional women's basketball leagues in the United States, such as the American Basketball League (1996-1998), have folded in part because of the popularity of the WNBA.

In 2001, the NBA formed a developmental league, the NBDL. The league currently has eight teams, but added seven more for the 2006-2007 season.

International basketball

The International Basketball Federation was formed in 1932 by eight founding nations: Argentina, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Portugal, Romania and Switzerland. At this time, the organization only oversaw amateur players. Its acronym, in French, was thus FIBA; the "A" standing for amateur.

Basketball was first included in the Olympic Games in 1936, although a demonstration tournament was held in 1904. This competition has usually been dominated by the United States, whose team has won all but three titles, the first loss in a controversial final game in Munich in 1972 against the Soviet Union. In 1950 the first FIBA World Championship for men was held in Argentina. Three years later, the first FIBA World Championship for Women was held in Chile. Women's basketball was added to the Olympics in 1976, with teams such as Brazil and Australia rivaling the American squads.

FIBA dropped the distinction between amateur and professional players in 1989, and in 1992, professional players played for the first time in the Olympic Games. The United States' dominance continued with the introduction of their Dream Team. However, with developing programs elsewhere, other national teams started to beat the United States. A team made entirely of NBA players finished sixth in the 2002 World Championships in Indianapolis, behind Yugoslavia, Argentina, Germany, New Zealand and Spain. In the 2004 Athens Olympics, the United States suffered its first Olympic loss while using professional players, falling to Puerto Rico (in a 19-point loss) and Lithuania in group games, and being eliminated in the semifinals by Argentina. It eventually won the bronze medal defeating Lithuania, finishing behind Argentina and Italy.

Worldwide, basketball tournaments are held for boys and girls of all age levels. The global popularity of the sport is reflected in the nationalities represented in the NBA. Players from all over the globe can be found in NBA teams. Chicago Bulls star forward Luol Deng is a Sudanese refugee who settled in Great Britain; Steve Nash, who won the 2005 and 2006 NBA MVP award, is Canadian; Kobe Bryant is an American who spent much of his childhood in Italy; Dallas Mavericks superstar and 2007 NBA MVP Dirk Nowitzki is German; All-Star Pau Gasol of the Memphis Grizzlies is from Spain; 2005 NBA Draft top overall pick Andrew Bogut of the Milwaukee Bucks is Australian; 2006 NBA Draft top overall pick Andrea Bargnani of the Toronto Raptors is from Italy; Houston Rockets Center Yao Ming is from China; Cleveland Cavaliers big man Zydrunas Ilgauskas is Lithuanian; and the San Antonio Spurs feature Tim Duncan of the U.S. Virgin Islands, Manu Ginobili of Argentina (like Chicago Bulls player Andrés Nocioni) and Tony Parker of France. (Duncan competes for the United States internationally, as the Virgin Islands did not field a basketball team for international competition until well after Duncan started playing internationally, and all U.S. Virgin Islands natives are United States citizens by birth.)

The all-tournament teams at the two most recent FIBA World Championships, held in 2002 in Indianapolis and 2006 in Japan, demonstrate the globalization of the game equally dramatically. Only one member of either team was American, namely Carmelo Anthony in 2006. The 2002 team featured Nowitzki, Ginobili, Peja Stojakovic of Yugoslavia (now of Serbia), Yao Ming of China, and Pero Cameron of New Zealand. Ginobili also made the 2006 team; the other members were Anthony, Gasol, his Spanish teammate Jorge Garbajosa and Theodoros Papaloukas of Greece. The only players on either team to never have joined the NBA are Cameron and Papaloukas.

Rules and regulations

- Main article: Rules of basketball

Measurements and time limits discussed in this section often vary among tournaments and organizations; international and NBA rules are used in this section.

The object of the game is to outscore one's opponents by throwing the ball through the opponents' basket from above while preventing the opponents from doing so on their own. An attempt to score in this way is called a shot. A successful shot is worth two points, or three points if it is taken from beyond the three-point arc which is 6.25 meters (20 ft 6 in) from the basket in international games and 23 ft 9 in (7.24 m) in NBA games.

Playing regulations

Games are played in four quarters of 10 (international) or 12 minutes (NBA). College games use two 20 minute halves while most high school games use eight minute quarters. Fifteen minutes are allowed for a half-time break, and two minutes are allowed at the other breaks. Overtime periods are five minutes long. Teams exchange baskets for the second half. The time allowed is actual playing time; the clock is stopped while the play is not active. Therefore, games generally take much longer to complete than the allotted game time, typically about two hours.

Five players from each team (out of a twelve player roster) may be on the court at one time. Substitutions are unlimited but can only be done when play is stopped. Teams also have a coach, who oversees the development and strategies of the team, and other team personnel such as assistant coaches, managers, statisticians, doctors and trainers.

For both men's and women's teams, a standard uniform consists of a pair of shorts and a jersey with a clearly visible number, unique within the team, printed on both the front and back. Players wear high-top sneakers that provide extra ankle support. Typically, team names, players' names and, outside of North America, sponsors are printed on the uniforms.

A limited number of time-outs, clock stoppages requested by a coach for a short meeting with the players, are allowed. They generally last no longer than one minute unless, for televised games, a commercial break is needed.

The game is controlled by the officials consisting of the referee ("crew chief" in the NBA), one or two umpires ("referees" in the NBA) and the table officials. For both college and the NBA there are a total of three referees on the court. The table officials are responsible for keeping track of each teams scoring, timekeeping, individual and team fouls, player substitutions, team possession arrow, and the shot clock.

Equipment

The only essential equipment in basketball is the basketball and the court: a flat, rectangular surface with baskets at opposite ends. Competitive levels require the use of more equipment such as clocks, scoresheets, scoreboard(s), alternating possession arrows, and whistle-operated stop-clock systems.

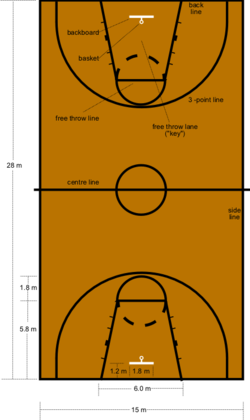

A regulation basketball court in international games is 28 by 15 meters (approx. 92 by 49 ft) and in the NBA is 94 by 50 feet (29 by 15 m). Most courts are made of wood. A steel basket with net and backboard hang over each end of the court. At almost all levels of competition, the top of the rim is exactly 10 feet (3.05 m) above the court and 4 feet (1.2 m) inside the baseline. While variation is possible in the dimensions of the court and backboard, it is considered important for the basket to be of the correct height; a rim that is off by but a few inches can have an adverse effect on shooting.

Violations

The ball may be advanced toward the basket by being shot, passed between players, thrown, tapped, rolled or dribbled (bouncing the ball while running).

The ball must stay within the court; the last team to touch the ball before it travels out of bounds forfeits possession. The ball-handler may not move both feet without dribbling, known as traveling, nor may he dribble with both hands or catch the ball in between dribbles, a violation called double dribbling. A player's hand cannot be under the ball while dribbling; doing so is known as carrying the ball. A team, once having established ball control in the front half of the court, may not return the ball to the backcourt. The ball may not be kicked nor struck with the fist. A violation of these rules results in loss of possession, or, if committed by the defense, a reset of the shot clock.

There are limits imposed on the time taken before progressing the ball past halfway (8 seconds in international and NBA; 10 seconds in NCAA and high school), before attempting a shot (24 seconds in the NBA; 35 seconds in NCAA), holding the ball while closely guarded (5 seconds), and remaining in the restricted area (the lane, or "key") (3 seconds). These rules are designed to promote more offense. Note: most high school games do not employ a shot clock.

No player may interfere with the basket or ball on its downward flight to the basket, or while it is on the rim (or, in the NBA, while it is directly above the basket), a violation known as goaltending. If a defensive player goaltends, the attempted shot is considered to have been successful. If a teammate of the shooter goaltends, the basket is cancelled and play continues with the defensive team being given possession.

Fouls

- Main articles: Personal foul, Technical foul

An attempt to unfairly disadvantage an opponent through physical contact is illegal and is called a foul. These are most commonly committed by defensive players; however, they can be committed by offensive players as well. Players who are fouled either receive the ball to pass inbounds again, or receive one or more free throws if they are fouled in the act of shooting, depending on whether the shot was successful. One point is awarded for making a free throw, which is attempted from a line 15 feet (4.5 m) from the basket.

The referee may use discretion in calling fouls (for example, by considering whether an unfair advantage was gained), sometimes making fouls controversial calls. The calling of fouls can vary between games, leagues and even between referees.

A player or coach who shows poor sportsmanship, for instance, by arguing with a referee or by fighting with another player, can be charged with a more serious foul called a technical foul. The penalty involves free throws (which unlike a personal foul, the other team can choose who they want to shoot the free throws) and varies between leagues. Repeated incidents can result in disqualification. Blatant fouls with excessive contact or that are not an attempt to play the ball are called unsportsmanlike fouls (or flagrant fouls in the NBA) and typically will result in ejection.

If a team surpasses a preset limit of team fouls in a given period (quarter or half) – four for NBA and international games – the opposing team is awarded one or two free throws on all subsequent fouls for that period, the number depending on the league. In the US college game if a team surpasses 7 fouls in the half the opposing team is awarded a one-and-one free throw (make the first you have a chance at a second). If a team surpasses 10 fouls in the half the opposing team is awarded two free throws on all subsequent fouls for the half. A player who commits five fouls, including technical fouls, in one game (six in some professional leagues, including the NBA) is not allowed to participate for the rest of the game, and is described as having "fouled out".

After a team has committed a specified number of fouls, it is said to be "in the penalty". On scoreboards, this is usually signified with an indicator light reading "Bonus" or "Penalty" with an illuminated directional arrow indicating that team is to receive free throws when fouled by the opposing team. (Some scoreboards also indicate the number of fouls committed.)

The number of free throws awarded increases with the number of fouls committed. Initially, one shot is awarded, but after a certain number of additional fouls are committed the opposing team may receive (a) one shot with a chance for a second shot if the first shot is made, called shooting "one-and-one", or (b) two shots. If a team misses the first shot (or "front end") of a one-and-one situation, the opposing team may reclaim possession of the ball and continue play. If a team misses the first shot of a two-shot situation, the opposing team must wait for the completion of the second shot before attempting to reclaim possession of the ball and continuing play.

If a player is fouled while attempting a shot and the shot is unsuccessful, the player is awarded a number of free throws equal to the value of the attempted shot. A player fouled while attempting a regular two-point shot, then, receives two shots. A player fouled while attempting a three-point shot, on the other hand, receives three shots.

If a player is fouled while attempting a shot and the shot is successful, typically the player will be awarded one additional free throw for one point. In combination with a regular shot, this is called a "three-point play" because of the basket made at the time of the foul (2 points) and the additional free throw (1 point). Four-point plays, while rare, can also occur.

Common techniques and practices

Positions and structures

Although the rules do not specify any positions whatsoever, they have evolved as part of basketball. During the first five decades of basketball's evolution, one guard, two forwards, and two centers or two guards, two forwards, and one center were used. Since the 1980s, more specific positions have evolved, namely:

- point guard: usually the fastest player on the team, organizes the team's offense by controlling the ball and making sure that it gets to the right player at the right time

- shooting guard: creates a high volume of shots on offense; guards the opponent's best perimeter player on defense

- small forward: often primarily responsible for scoring points via cuts to the basket and dribble penetration; on defense seeks rebounds and steals, but sometimes plays more actively

- power forward: plays offensively often with his back to the basket; on defense, plays under the basket (in a zone defense) or against the opposing power forward (in man-to-man defense)

- center: uses size to score (on offense), to protect the basket closely (on defense), or to rebound.

The above descriptions are flexible. On some occasions, teams will choose to use a three guard offense, replacing one of the forwards or the center with a third guard. The most commonly interchanged positions are point guard and shooting guard, especially if both players have good leadership and ball handling skills.

There are two main defensive strategies: zone defense and man-to-man defense. Zone defense involves players in defensive positions guarding whichever opponent is in their zone. In man-to-man defense, each defensive player guards a specific opponent and tries to prevent him from taking action.

Offensive plays are more varied, normally involving planned passes and movement by players without the ball. A quick movement by an offensive player without the ball to gain an advantageous position is a cut. A legal attempt by an offensive player to stop an opponent from guarding a teammate, by standing in the defender's way such that the teammate cuts next to him, is a screen or pick. The two plays are combined in the pick and roll, in which a player sets a pick and then "rolls" away from the pick towards the basket. Screens and cuts are very important in offensive plays; these allow the quick passes and teamwork which can lead to a successful basket. Teams almost always have several offensive plays planned to ensure their movement is not predictable. On court, the point guard is usually responsible for indicating which play will occur.

Defensive and offensive structures, and positions, are more emphasized in higher levels in basketball; it is these that a coach normally requests a time-out to discuss.

Shooting

Shooting is the act of attempting to score points by throwing the ball through the basket. While methods can vary with players and situations, the most common technique can be outlined here.

The player should be positioned facing the basket with feet about shoulder-width apart, knees slightly bent, and back straight. The player holds the ball to rest in the dominant hand's fingertips (the shooting arm) slightly above the head, with the other hand on the side of the ball. To aim the ball, the player's elbow should be aligned vertically, with the forearm facing in the direction of the basket. The ball is shot by bending and extending the knees and extending the shooting arm to become straight; the ball rolls off the finger tips while the wrist completes a full downward flex motion. When the shooting arm is stationary for a moment after the ball released, it is known as a follow-through; it is incorporated to maintain accuracy. Generally, the non-shooting arm is used only to guide the shot, not to power it.

Players often try to put a steady backspin on the ball to deaden its impact with the rim. The ideal trajectory of the shot is somewhat arguable, but generally coaches will profess proper arch. Most players shoot directly into the basket, but shooters may use the backboard to redirect the ball into the basket.

The two most common shots that use the above described set up are the set shot and the jump shot. The set shot is taken from a standing position, with neither foot leaving the floor, typically used for free throws. The jump shot is taken while in mid-air, near the top of the jump. This provides much greater power and range, and it also allows the player to elevate over the defender. Failure to release the ball before returning the feet to the ground is a traveling violation.

Another common shot is called the layup. This shot requires the player to be in motion toward the basket, and to "lay" the ball "up" and into the basket, typically off the backboard (the backboard-free, underhand version is called a finger roll). The most crowd-pleasing, and typically highest-percentage accuracy shot is the slam dunk, in which the player jumps very high, and throws the ball downward, straight through the hoop.

A shot that misses both the rim and the backboard completely is referred to as an air ball. A particularly bad shot, or one that only hits the backboard, is jocularly called a brick.

Rebounding

- Main article: Rebound (basketball)

The objective of rebounding is to successfully gain possession of the basketball after a missed field goal or free throw, as it rebounds from the hoop or backboard. This plays a major role in the game, as most possessions end when a team misses a shot. There are two categories of rebounds: offensive rebounds, in which the ball is recovered by the offensive side and does not change possession, and defensive rebounds, in which the defending team gains possession of the loose ball. The majority of rebounds are defensive, as the team on defense tends to be in better position to recover missed shots.

Passing

- See also: Assist (basketball)

A pass is a method of moving the ball between players. Most passes are accompanied by a step forward to increase power and are followed through with the hands to ensure accuracy.

A staple pass is the chest pass. The ball is passed directly from the passer's chest to the receiver's chest. A proper chest pass involves an outward snap of the thumbs to add velocity and leaves the defense little time to react.

Another type of pass is the bounce pass. Here, the passer bounces the ball crisply about two-thirds of the way from his own chest to the receiver. The ball strikes the court and bounces up toward the receiver. The bounce pass takes longer to complete than the chest pass, but it is also harder for the opposing team to intercept (kicking the ball deliberately is a violation). Thus, players often use the bounce pass in crowded moments, or to pass around a defender.

The overhead pass is used to pass the ball over a defender. The ball is released while over the passer's head.

The outlet pass occurs after a team gets a defensive rebound. The next pass after the rebound is the outlet pass.

The crucial aspect of any good pass is being impossible to intercept. Good passers can pass the ball with great accuracy and touch and know exactly where each of their teammates like to receive the ball. A special way of doing this is passing the ball without looking at the receiving teammate. This is called a no-look pass.

Another advanced style of passing is the behind-the-back pass which, as the description implies, involves throwing the ball behind the passer's back to a teammate. Although some players can perform them effectively, many coaches discourage no-look or behind-the-back passes, believing them to be fundamentally unsound, difficult to control, and more likely to result in turnovers or violations.

Dribbling

- Main article: Dribble

Dribbling is the act of bouncing the ball continuously, and is a requirement for a player to take steps with the ball. To dribble, a player pushes the ball down towards the ground rather than patting it; this ensures greater control.

When dribbling past an opponent, the dribbler should dribble with the hand farthest from the opponent, making it more difficult for the defensive player to get to the ball. It is therefore important for a player to be able to dribble competently with both hands.

Good dribblers (or "ball handlers") tend to bounce the ball low to the ground, reducing the travel from the floor to the hand, making it more difficult for the defender to "steal" the ball. Additionally, good ball handlers frequently dribble behind their backs, between their legs, and change hands and directions of the dribble frequently, making a less predictable dribbling pattern that is more difficult to defend, this is called a crossover which is the most effective way to pass defenders while dribbling.

A skilled player can dribble without watching the ball, using the dribbling motion or peripheral vision to keep track of the ball's location. By not having to focus on the ball, a player can look for teammates or scoring opportunities, as well as avoid the danger of someone stealing the ball from him/her.

Height

At the professional level, most male players are above 1.90 meters (6 ft 3 in) and most women above 1.70 meters (5 ft 7 in). Guards, for whom physical coordination and ball-handling skills are crucial, tend to be the smallest players. Almost all forwards in the men's pro leagues are 2 meters (6 ft 6 in) or taller. Most centers are over 2.1 meters (6 ft 10 in) tall. According to a survey given to all NBA teams, the average height of all NBA players is just under 6 ft 7 in (2.01 m), with the average weight being close to 222 lb (101 kg). The tallest players ever in the NBA were Manute Bol and Gheorghe Mureşan, who were both 2.31 m (7 ft 7 in) tall. The tallest current NBA player is Yao Ming, who stands at 2.26 m (7 ft 6 in).

The shortest player ever to play in the NBA is Muggsy Bogues at 1.60 meters (5 ft 3 in). Other short players have thrived at the pro level. Anthony "Spud" Webb was just 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m) tall, but had a 42-inch (1.07 m) vertical leap, giving him significant height when jumping. The shortest player in the NBA today is Earl Boykins at 5 feet 5 inches (1.65 m). While shorter players are often not very good at defending against shooting, their ability to navigate quickly through crowded areas of the court and steal the ball by reaching low are strengths.

Variations and similar games

- Main article: Variations of basketball

Variations of basketball are activities based on the game of basketball, using common basketball skills and equipment (primarily the ball and basket). Some variations are only superficial rules changes, while others are distinct games with varying degrees of basketball influences. Other variations include children's games, contests or activities meant to help players reinforce skills.

Wheelchair basketball is played on specially designed wheelchairs for the physically impaired. The world governing body of wheelchair basketball is the International Wheelchair Basketball Federation [5] (IWBF). Water basketball, played in a swimming pool, merges basketball and water polo rules. Beach basketball is played in a circular court with no backboard on the goal, no out-of-bounds rule with the ball movement to be done via passes or 2 1/2 steps, as dribbling is not allowed.[6]

There are many variations as well played in informal settings without referees or strict rules. Perhaps the single most common variation is the half court game. Only one basket is used, and the ball must be "cleared" - passed or dribbled outside the half-court or three-point line - each time possession of the ball changes from one team to the other. Half-court games require less cardiovascular stamina, since players need not run back and forth a full court. Half-court games also raise the number of players that can use a court, an important benefit when many players want to play.

A popular version of the half-court game is 21. Two-point shots count as two points and shots from behind the three-point line count three. A player who makes a basket is awarded up to three extra free throws (or unlimited if you are playing "all day"), worth the usual one point. When a shot is missed, if one of the other players tips the ball in with two while it is in the air, the score of the player who missed the shot goes back to zero, or if they have surpassed 13, their score goes back to 13. This is called a "tip". If a missed shot is "tipped" in, but the player who tips it in only uses one hand, then the player who shot it is out of the game and has to catch an air ball to get back in. The first player to reach exactly 21 points wins. If they go over, their score goes back to 13. Jonathan